Cultural Center of the Philippines

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF

PHILIPPINE ART

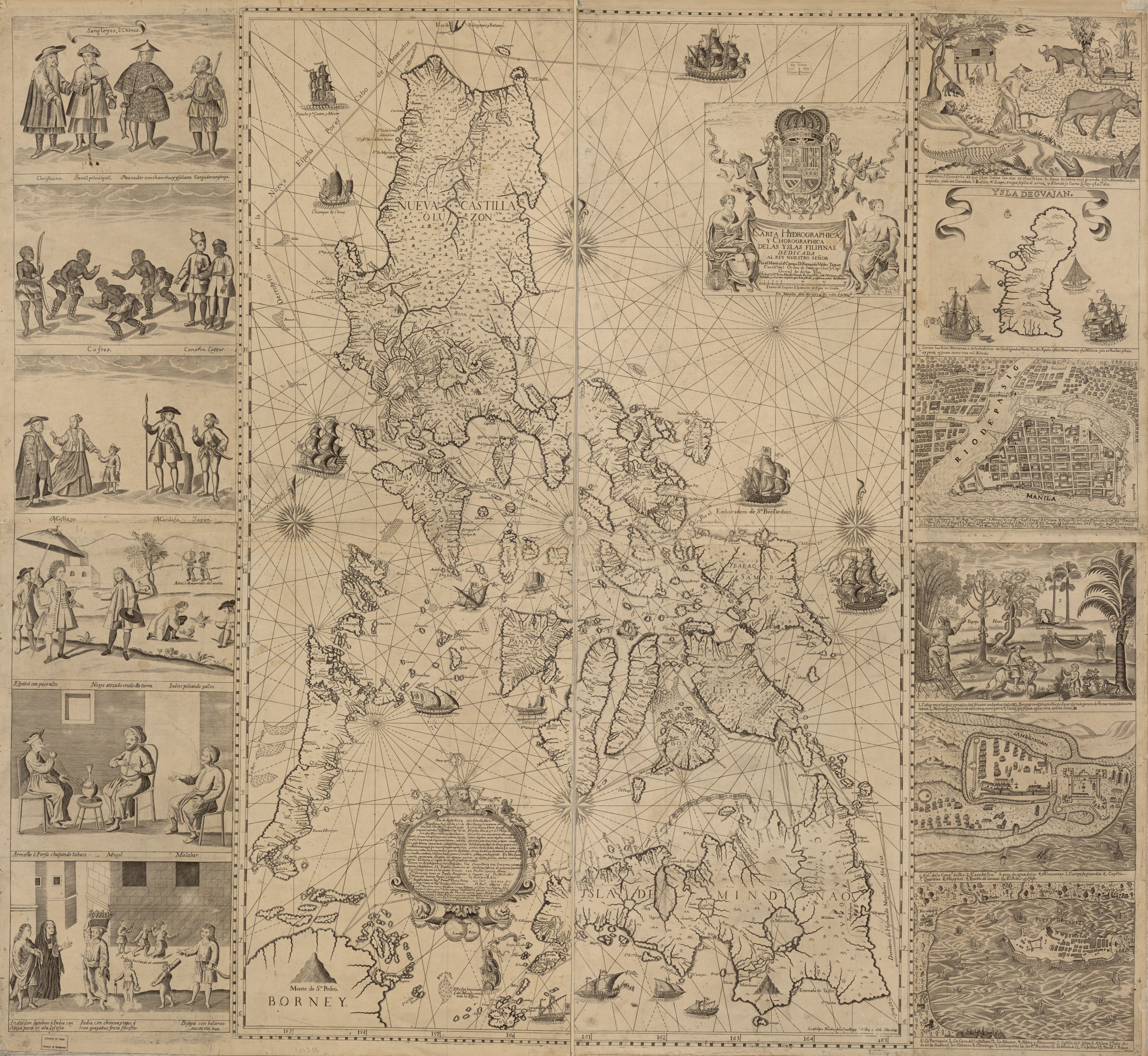

[Murillo Velarde Map of 1734] Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas

(Aquatic and Regional Map of the Philippine Islands) aka Pedro Murillo Velarde Map of the Philippines / 1734 / Engraving on copper / 68.58 x 106.68 cm / Artists: Nicolas de la Cruz Bagay and Francisco Suarez / Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress collection

The project began with a royal request for an accurate map on 1 Jun 1729. Gov-Gen Fernando Valdes Tamon assigned the Jesuit cartographer Velarde to chart the map, who in turn asked Bagay and Suarez to execute it. Due to its size, it had to be struck on several copperplates then assembled together. Bagay did the map and two other panels, each consisting of three views of life in Manila. Suarez also did two panels similarly consisting of three scenes each, one on top of the other. Each panel was accommodated in one copperplate. In examples where the entire work is intact, the map is flanked by the four panels, each of three vignettes.

The artistic finesse and maturity of the map section is well evident in the symbolic frame bearing the map’s title and the details of the dedication. The frame is adorned with two seated muses raising with their right hands a drape on which the details of the commission are inscribed. This cloth is topped by the royal Spanish coat of arms held up by trumpeting putti. Other conventional details in the map are vessels sailing in the waters surrounding the islands. The two panels, each containing three vignettes drawn by Bagay, all involve multifigure scenes. All the scenes are annotated with inscriptions underneath. The topmost vignette of the panel shows Chinese people in costumes denoting their station. The first is dressed in 18th-century European costume including a flowing cape, a wide-brimmed hat, a curly wig, and a beard; the second is the local merchant also garbed in European-inspired dress sporting a salakot (woven hat) and a fan; the third is a fisherman holding his catch; and the fourth is a cargador with several rolls of rope. The middle vignette of the first panel shows four Aeta, three of whom are dancing while one holding a bow is watching them; these Aeta are labeled “cafres.” Also in this picture are a “Canarin” or a native of Canara and an Indian sailor, personages frequently seen in Manila because they served in Indian trading boats. The lowermost vignette shows a mixed marriage as portrayed by a European in 18th-century court fashion, his bejewelled indio (Christianized native) wife, and their mestizo son. Also in the picture is a native of Ternate with his lance, shield, and dagger; he listens to a Japanese laborer in tight breeches and armed with a samurai sword. The topmost vignette of the second plate shows two Spaniards conversing, one of whom is followed by a servant who carries an umbrella to shade his master. Both gentlemen wear fashionable 18th-century European clothes consisting of tight knee-length breeches and wide-cuffed coats; they also sport curly wigs. In the background are two indios coaxing their roosters to a fight; behind them are Aeta, one of whom has his arrow aimed at an animal under the tree. The middle vignette shows an interior where a Persian, a Mongolian, and a Malabar converse. The Persian sucks opium from a waterpipe. The lowermost vignette of the second panel shows a cityscape of Intramuros. In the foreground are several indios, left to right: an indio with a cape, called lambon; an indio with black veil, called cobija, on her way to mass; a woman carrying a basket of guavas; two seminaked children; and a man labeled as a Visaya, holding a bolo. In the background, a couple dance the comintang in front of a rusticated building to a tune played on the bandurria by a third person.

The Suarez vignettes also number six, presented in threes in two plates. While Bagay’s scenes consist of figures simply situated against an empty or near-empty background, Suarez’s are elaborate, complex, and extremely detailed scenes. This shows that the latter was a veteran in the job, his career antedating Bagay by 15 years. The topmost vignette of the first panel is a scene introducing the most common trees and plants in the Philippines. In the right foreground, a coconut palm is balanced by a clump of bamboo on the left. A man, standing on a ladder against the bamboo, is about to strike it with his bolo. In the middle ground are a papaya tree and a jackfruit tree with overhanging fruits on its trunks. In the middle foreground is a man astride a donkey, with a child beside him showing a bat that he has caught. In the middle ground, two men carry a sick person reclined on a hammock. These scenes show that Suarez mastered the linear perspective. The middle vignette of the second panel depicts an aerial view of the port of Zamboanga. The lowermost panel is a view of the Cavite port. The topmost vignette of the second panel by Suarez is a tilted rural scene depicting a crocodile in the foreground and two farmers, one tilling the soil with the aid of a carabao and the other using a carabao to pull a sled. In the middle ground stands a tree from which hangs a cobra that is about to devour a pig; the snake is labeled “sawa.” The middle vignette displays a map of Guam. The island is surrounded by water in which sail galleons and native boats. The lowermost vignette displays a map of Intramuros, the Pasig River, and the districts across.

Bagay and Suarez were certainly chosen for the project because of their skills. Proud of their accomplishments, they signed “Indio Tagalo” (Tagalog native) after their names. Their successful projects prompted Father Velarde to remark that in Manila “there are excellent embroiderers, painters, silversmen, and engravers whose lines had no equal in the entire Indies.”

The 1734 Murillo Velarde map would eventually be revised in the succeeding years based on the changing fortunes of the Jesuit order in the 18th and 19th centuries. The 1744 reprint of the map shows the symbolic frame moved in the upper portion with a revised text, while an image of San Francisco Xavier riding on a seahorse is depicted in the lower part of the map, signifying the Jesuit missions in Mindanao. The 1788 version shows the absence of the text “la Compania de Jesus,” which reflected the Jesuit’s loss of power due to their expulsion in 1768, while an ornamented frame replaced the images of the inhabitants of the islands. In 1859, the phrase “la Compania de Jesus” eventually returned to the reprinted edition, following the return to power of the Jesuits in the Philippines.

Written by Santiago A. Pilar / Updated by Cecilia S. De La Paz