Cultural Center of the Philippines

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF

PHILIPPINE ART

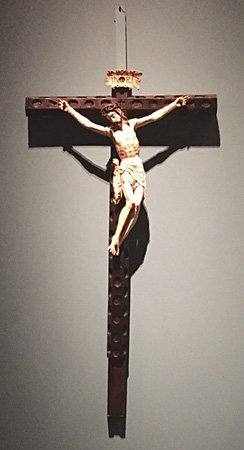

[Ivory Crucified Christ]

Late 16th to early 17th century / Ivory / 77 x 68 cm / Artist: anonymous / Hall of Philippine Religious Images, University of Santo Tomas Museum

At the end of this hall of the University of Santo Tomas Museum hangs an ivory image of the [Crucified Christ]. It is considered the largest and the finest ivory crucifix ever made in the Philippines. The image, attached to a wooden cross, is a representation of the recently expired Christ or Cristo expirante, indicated by its head which is hanging down. Despite this, the eyes are not completely shut, and the mouth is slightly open, seemingly awaiting its last breath. The outstretched arms of Christ sag as the body is pulled down by its own weight. However, the horizontal curve of the spread arms complemented by the vertical curvature of the limp body, gives the Christ figure a poised, even graceful appearance, which appears to belie the violence of the crucifixion. The fact is, many Philippine crucifixes are depicted as generally “placid,” rarely showing extreme agony. The face is calm, evoking a gentle pathos. This quiet suffering is read by some as a projection of the colonized people’s own suffering vicariously taken on by Christ.

The artist has also realistically carved out the musculature of the figure. The arms are taut, ligaments visible, as they strain to carry the weight of the body. The contours of the lean torso are clearly defined, with the ribs subtly visible beneath the flesh. Also visible is the open wound at the side, its bleeding reduced to a trickle. Christ’s otherwise naked body is wrapped in a crumpled loincloth, seemingly put together in haste, and bound loosely by a piece of knotted rope. Its folds lend respite to the otherwise strong verticality of the figure. The lower limbs are bent at the knees to emphasize the wounds from Christ’s many falls. The feet overlap and are pegged to the cross by a single penetrating nail, the toes still splayed, even in death, conveying the trauma of pain. It has also been remarked that this particular crucifix’s attenuated forms may have been influenced by the art of the 16th-century painter El Greco.

The [Crucified Christ], from the head with its meticulously carved hair and crown of thorns, down to the nailed feet, is carved from a single piece of ivory, except for the arms that have been sculpted from separate pieces and are detachable from the body. The cross, which is in wood, has small holes all over, probably used as receptacles for small silver or gold relics or ex votos, or offerings made to the church to fulfill a vow.

Philippine religious ivories, such as this crucifix, not only adorned the churches and family altars in the country, but were also exported to Macau, India, Mexico, and Spain.

Written by Marilyn R. Canta

Sources

Bunag-Gatbonton, Esperanza. 1979. A Heritage of Saints. Manila; Hongkong: Editorial Associates.

———. 1983. Philippine Religious Carvings in Ivory. Manila: Intramuros Administration, Ministry of Human Settlements.

Jose, Regalado Trota, and Ramon N. Villegas. 2004. Power, Faith, Image: Philippine Art in Ivory from the 16th to the 19th Century. Makati

City: Ayala Foundation.

Macairan, Evelyn. 2013. “UST Exhibits Largest Ivory Crucifix in Phl.” The Philippine Star, 29 Jul.

Martin, Esmond, Chryssee Martin, and Lucy Vigne. 2011. “The Importance of Ivory in Philippine Culture.” Pachyderm, Jul/Dec.

UST Museum. 2010. “Hall of Philippine Religious Images.” Accessed 11 Jun 2014.

Vardeleon, Sherwin Marion T. 2013. “Controversial Ivory Icon, ‘Finest and Largest,’ on Exhibit at UST Museum.” Inquirer.net, 23 Sep.

Villalon, Augusto. 2005. “Philippine Ivory Craft Is Part of World Art History.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 18 Jul, D4.

Zobel de Ayala, Fernando. 1963. Philippine Religious Imagery. Photos by Nap C. Jamir. Manila: Ateneo de Manila.