Cultural Center of the Philippines

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF

PHILIPPINE ART

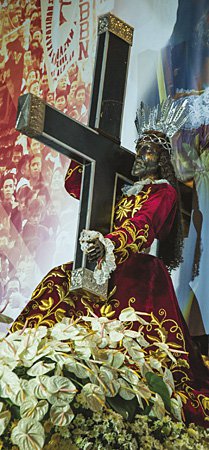

[Black Nazarene of Quiapo] Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno (N.P.J.N)

(Our Father Jesus of Nazarene) aka Poong Itim na Nazareno (Black Lord Nazerene) or Mahal na Poong Nazareno ng Quiapo (Nazarene of Quiapo) or Black Nazarene / Early 1600s / Original in darkwood; replicas in molave (body) and batikuling wood (head) / Life-size / Minor Basilica of the Black Nazarene, Parish of Saint John the Baptist, Quiapo, Manila

Crafted in Mexico, the image of the Black Nazarene was brought to the Philippines by the Augustinian Recollects on 31 May 1606 and initially enshrined in the church of San Juan Bautista in Bagumbayan. Upon the request of then archbishop of Manila Basilio Sancho de Santa Justa, the image was transferred to the church of Quiapo in 1787. This historic transfer and the feast of the Black Nazarene are commemorated every 9th of January in a grand procession called the traslacion or transfer (Minor Basilica of the Black Nazarene 2014a).

The Black Nazarene is the representation in a maroon robe of a dark-skinned Christ carrying the cross on his right shoulder, positioned with one knee on the ground and looking heavenward with agony. Expressionist in style, it is a solitary image depicting Christ falling to the ground on the way to His crucifixion on Calvary. The image wears a crown of thorns, representing Jesus’s mockery. Three gold rays, called potencias, emanate from the image’s head, symbolizing Christ’s power and divinity. The image has a detachable head and movable arms and shoulders, with molave and batikuling wood used to replace the presumed original mahogany wood. In the 1990s, the original head of the image was transferred to a new body and permanently enshrined on the basilica’s main altar for preservation purposes. The original body in return was refurbished with a replica of the head and is the one brought out in processions (Bonilla 2006, 106-7).

The dark complexion of the image has spurred many theories, one of which is that it was made to reflect the color of native Mexicans (Catapang 1937). Another theory says it was a casualty of a fire that broke out on the galleon during its voyage to the Philippines (dela Vega 2013). Carved out of dark wood, the image darkened further due to aging and constant anointing with balsamic oil and perfume. The dark complexion and the attitude of suffering, together with the reputation of the image as miraculous, have made the image popular and endearing to many Filipinos. Devotees articulate that being dark-skinned and striving to bear the difficulties of life are Filipino traits. Devotion to the Black Nazarene is observed every Friday, especially the first Fridays of the month, during which hundreds of thousands of people flock to Quiapo Church (Bonilla 2006, 107-8).

The number of devotees of the Black Nazarene continues to grow. An estimated 10 million devotees joined the 2014 procession (Severino and Legaspi 2014). Unfolding over several hours, the procession used to originate from and end at the basilica. But on the celebration of the 400th year of the arrival of the Black Nazarene in 2007 and thereafter, the procession started from Rizal Park and wound its way, over Quezon Bridge, to Quiapo church, reenacting the original transfer of the image from Intramuros to Quiapo in 1787 (Santos 2009). The procession proceeds at an extremely slow pace, lasting for 22 hours in 2012 (Andrade and Santos 2012). The Black Nazarene’s traslacion is characterized by an overwhelmingly passionate display of popular devotion. Most participants aim to hold the ropes that pull the float of the image along. Some devotees attempt to board the float to get an opportunity to touch the image to sacralise their handkerchiefs. As one of the most popular religious icons in the Philippines, the image of the Black Nazarene has been associated with healing, has been used as an image for amulets, and has inspired narratives of salvation among its devotees.

Written by Dino Carlo S. Santos

Sources

Andrade, Jeannette I, and Matikas Santos. 2012. “‘Longest Ever’ Black Nazarene Procession Ends.” Inquirer.net, 10 Jan. Accessed 12 May 2014. http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/ 125633/longest-ever-black-nazarene-procession-ends.

Bonilla Celia M. 2001. “The Performance of Faith: Aesthetics of Devotion in Quiapo.” 2001. MA thesis, University of the Philippines Diliman.

———. 2006. “Devotion to the Black Nazarene as an Aesthetic Experience.” In Quiapo: Heart of Manila, edited by Fernando Nakpil Zialcita, 96-124. Manila: The Cultural Heritage Studies Program, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Ateneo de Manila University; Metropolitan Museum of Manila.

Catapang, Vicente. 1937. Brief History of the Quiapo Church and Its Miraculous Image, The Black Nazarene. Manila.

dela Vega, Robby V. 2013. “Ang Dalawang Nazareno ng Maynila.” Chronicles of a Teacher, Thoughts of a Frustrated Local Historian (blog). Posted 4 Jan. http://chroniclesandfrustrations.blogspot.com/2013/01/angdalawang-nazareno-ng-maynila.html.

Minor Basilica of the Black Nazarene. 2014a. “Devotion to the Black Nazarene.” http://www.quiapochurch.com/index.php/about/devotion-to-the-black- Accessed 12 May.

———. 2014b. “The Image.” http://www.quiapochurch.com/index.php/about/the-image. Accessed 12 May.

———. 2014c. “Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno.” http://www.quiapochurch.com/index.php/about/nuestro-padre-jesusnazareno. Accessed 12 May.

Santos, Tina. 2009. “Nazarene Procession to Begin at Luneta.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 3 Jan. Accessed 12 May 2014. http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/breakingnews/metro/view/20090103-181226/Nazarene-procession-to-begin-at-Luneta.

Severino, Howie, and Amita Legaspi. 2014. “10M People Join Peaceful Nazareno Festivities; No Deaths, Major Injuries.” GMA News Online, 10 Jan. Accessed 12 May 2014. http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/343225/news/metromanila/10m-people-join-peaceful-nazareno-festivitiesno-deaths-major-injuries.